Overview of Story Structure

Story structure is something which helps elevate your story. It becomes the base for your story to build upon. It doesn’t dictate what the story is going to be rather it acts as a road map. We should not be following the story structure too strictly other it may backfire. It should act like a frame work to help identify flaws and ensure natural flow of the story. When feeling something isgoing off while writing, story structure help identify and resolve the issue.

Escalation: The driving force of Conflict

What is more important than anything in any story, a framework, sequence of events taking place? It is the conflict. The conflict and the struggle make the story. A compelling story is when the characters struggle, strive and are forced to make changes, learn from mistakes/setbacks and get back back strong. Stakes need to be increased inorder to achive these changes. Sanderson explains how to escalate using a method “Yes, But / No, And”. The character attempts to solve a problem (Yes), but it comes with complications. Or, they fail (No), and things get even worse.

Star Wars example.

Does Luke get off Tatooine? Yes, but the ship’s captain is a smuggler with ulterior motives. Do they reach their destination safely? No, and they’re captured by the Death Star.

Each step escalates, driving the narrative forward and keeping readers engaged. The beauty of escalation is its ability to show character growth. As Luke’s challenges increase, so does his understanding of the Force, his role in the Rebellion, and his internal transformation (in other words, his character arc).

Escalations need to be in a gradual manner, a step by step approach. What happens if we suddenly escalate the stakes and the protagonist somehow powers up and saves everyone? it doesn’t feel too satisfactory and payoff is feels off. instead gradual escalation builds up emotion, we are connected to the character, we feel the attachment, we root for the character. When the final payoff happens we are left with an enormous amount of satisfaction.

Story Circles and the Hero’s Journey

Joseph Campbell’s monomyth is the most famous narrative structure, the hero’s journey. But in this article we are going to consider Dan Harmon’s story circle which Sanderson says is more flexible and simpler. The circle begins with a character in a state of ignorance or comfort, who is thrust into an adventure, faces trials, gains new knowledge, and returns home transformed.

Key Moments in the Story Circle:

Departure: The character leaves their comfort zone.

Trials: They encounter escalating obstacles that force growth.

Crisis: The character faces their darkest moment or greatest challenge.

Transformation: They gain the knowledge or power they need to succeed.

Return: The character brings their new understanding back home, changed.

Whatever genre you are going to write be it character driven or epic fantasy, progression and transformation should be clear.

The Try-Fail Cycle: Mastering Discovery Writing

Discovery writing is something where there is no particular outlining. It is a technique where the writer allows for the plot and characters to develop organically. The cycle goes like this: Before a character can achieve their goal, they should encounter multiple failures, each more challenging than the last. The failures should arise naturally from the plot, forcing the character to adapt and grow.

How the Try-Fail Cycle Works:

Attempt #1: The character tries the obvious solution, but it fails.

Attempt #2: They try a more complex or creative approach, but it also fails, often because of an internal flaw or external complication.

Attempt #3: Success, but only after overcoming significant obstacles.

Here the character’s limitations are revealed, the villains strengths are known and a lack of knowledge is also seen. This helps shape the protagonist to face the final obstacle. New subplots can be introduced and deepen the worldbuilding. Example: Lets use Star Wars to illustrate the Try-Fail cycle in action.

First Attempt: Luke struggles to control the Force during his training.

Second Attempt: He improves but overestimates his abilities, leading to failure in key moments.

Third Attempt: He finally succeeds after facing his fears and accepting his limitations.

Avoiding Plot Holes:The Art of Hanging a Lantern

plot holes are pretty commonly faced by any writer during the writing phase. If we do not address these plot holes, users are generally taken aback and are no more involved in the story. They keep circling back to that one unexplained event. To hang a lantern on something means acknowledging the issue within the narrative itself, often through a character’s dialogue or internal monologue. You typically see this on the stage. Maybe a portion of the set is rougher than the rest… the characters might point out an old lantern in that section that hasn’t worked in years. This implies to the audience that the writer knows that there’s something there, but it’s not important for you to pay attention to as an audience member. It keeps them in the story.

Example: The Survival of Police Officers in The Dark Knight Rises

One of the significant plot holes in The Dark Knight Rises (there are many) involves Bane trapping over a thousand police officers underground for months. The mystery is how they survived, and when they eventually escape, why do they emerge clean-shaven with neatly pressed uniforms? But even before all of that, why would Commissioner Gordon send all of the police underground in the first place?

The Major Dramatic Question: Your Story’s Core

Every story should answer a dramatic major question. In Star Wars, the question is whether Luke will become a Jedi and defeat the Empire. In Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, it’s whether Indy will find the Ark before the Nazis do.

The question should be clear by the end of first act. It should be the driving force for the plot to move forward and make audience/readers invest into the story. This question also helps bring subplot and character arcs together ensuring each element of the story contribute to the ultimate finale.

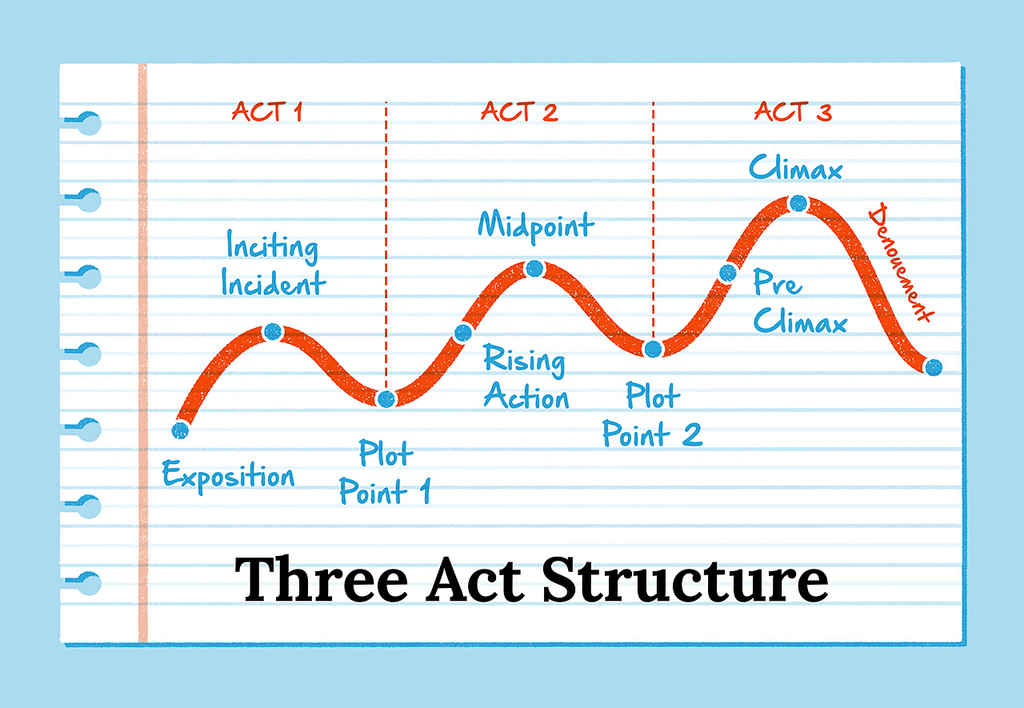

The Three-Act Structure: Chasing a Climactic Ending

The three act structure is the most basic framework used in every story.

Act One: Introduce the status quo and the inciting incident.

Act Two: Escalate the conflict through failures, complications, and rising stakes.

Act Three: Deliver the climactic resolution and tie up loose ends.

Example: Star Wars

Let’s look at this through the lens of Star Wars one more time!

Act One: Luke’s life on Tatooine is disrupted when he discovers the message from Princess Leia.

Act Two: He joins the Rebellion, faces obstacles, and begins his training.

Act Three: The final battle against the Death Star.

Final Thoughts

Understanding the basic principles on how to use the said frameworks or structures to help elevate the story is the key to learning. There is no definite way to write a story. All these things need to help achieve the final goal of telling a beautiful story which gives a satisfaction to the audience. Given the opportunity one should break from the conventional norms of writing a story and experiment. More and more practice, reading different techniques and ways of writing, analyzing a lot of different stories written can help in improving and identify your style of writing.

Never miss a story from us, subscribe to our newsletter

Never miss a story from us, subscribe to our newsletter